Ray

26th April 1917 Thursday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“I started work again on the 26th April under Major Louden at the casino on the sea-front which was connected with a huge hospital. I was put in charge of two wards, with over 40 patients in one, and about half that number in the other. Most of the cases were suffering from rheumatism and trench fever. All were medical cases. Four days later, I got 60 new cases into my wards. I was kept busy all morning, but was able to get the rest of the day mostly to myself, except when I was orderly officer.

Tea at ‘Topsy’s’ was the favourite afternoon jaunt, and at night dinner at the Hotel Normandie followed by a visit to the ‘Follies Bergeres’ was quite the thing to do!

The ‘Maison Blanch’ outside Havre was another good spot for dinner, and a Dr Simey and I used to walk out there often in the evening, and have a bite of food.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

25th April 1917 Wednesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“I wasn’t fit again until 26th April as I had a sharp attack and developed a nasty nasal catarrh afterwards which kept me back. I was extremely comfortable in hospital – well-fed and well cared for. I was allowed out of bed at the end of a week when my temperature settled. I had walks every day into town, and along the promenade with some of the other hospital patients. The weather was generally warm and sunny, so that we enjoyed these walks very much.

A favourite walk was down to the harbour where we watched the French aeroplanes leaving for, and arriving back from their patrols. Another good walk was along the top of the cliffs where one got a grand view of the open sea.”

Today in the 21st century it is the young, elderly and weak who are most at risk from dying from flu. In 1918 the year after Douglas contracted influenza a particularly aggressive strain of the disease was killing healthy young people. This outbreak became known as Spanish flu due to wartime censorship which neutral Spain wasn’t affected by. Their newspapers were free to report the reality giving the false impression that Spain was more severely affected than other regions particularly because of the severe illness contracted by the king Alfonso XIII. The Spanish called it the Naples Soldier. We should also remember that the disease that killed more people between 1918 and 1920 than the whole of World War One in modern times would have been largely controlled by cheap and widely available medicines such as paracetamol.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

17th April 1917 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

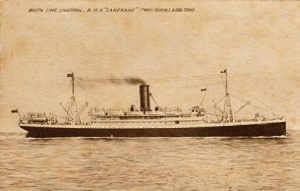

“The hospital ship “Lanfranc” was torpedoed off Havre on the 17th April. She had 400 German prisoners on board. Next day some of her lifeboats and the bodies of several nurses were washed ashore at Havre.”

Douglas’s figure of 400 German prisoners seems to be inaccurate as reports following the sinking at 8pm on the 17th April speak of 167 wounded German prisoners, 234 wounded British soldiers, 52 medical staff and 123 crew. The discrepancy in casualties is probably official propaganda. It would have been normal to exaggerate the figures of casualties to whip up anti-German sympathies.

Of the 576 persons onboard that evening only 34 lost their lives, 14 British wounded, 15 German wounded and 5 crew, the ship sank in just over 1 hour.

HMHS Lanfranc would have been flying the Red Cross flag and sporting green, red and white livery with a red cross on its sides as stipulated by the Hague Convention which was brought into effect in 1907. Hospital ships were required to pick up casualties of all nationalities and were supposed to be immune from attack. The fact that the ship was hit by a torpedo means that its sinking was intentional. In January 1917 the German Government had accused the Allies of using hospital ships to transport troops and medical supplies, adding that no Allied hospital ships would be tolerated within certain areas.

A pamphlet entitled “The War on Hospital Ships” published in 1917 from eyewitness accounts has more information about these terrible incidents including much about HMHS Lanfranc and SS Donegal which was lost on the same day.

An eyewitness account of the sinking from one of the British officers on board (page 13 on the above link) was published in the Daily Telegraph on 23 April 1917. That edition of the Telegraph will be available to view on the following link on 23 April 2017. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/ww1-archive/

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

26th March 1917 Monday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

After immediately signing on again for another tour of duty, this time in Egypt, Douglas’s sojourn in Scotland came to an end. However, Egypt in the sun became an unfulfilled fantasy. The sun was swapped for more mud and rain as orders came to report back to the Western Front.

“On the 26th I was relieved by a Capt. MacDonald, and proceeded to France via London, Southampton and Havre. Whilst awaiting in the rest camp at Havre to be sent up to the Front, I developed influenza, and was carted off to the Officers’ Hospital in Havre. It was a most comfortable hospital in a large mansionhouse. Col Babington D.S.O., was in charge, and I was put into a nice sunny ward. Next bed to me was a Mr Merrylees – a Y.M.C.A. worker – from Paisley. He had a bad dose of bronchitis, and was glad to lie in bed, being an elderly man.”

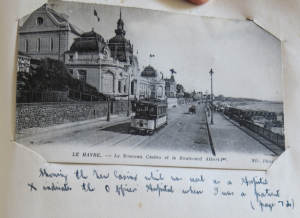

Showing the New Casino which was used as a hospital. X indicates the Officers’ Hospital where I was a patient

At the time, large hotels and buildings like schools and casinos were an obvious choice for wartime hospitals with their large rooms and large bright windows.

Today’s Le Havre leaves no trace of the Casino or the Officers’ hospital, the modern esplanade of Boulevard Albert has been totally modernised.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

13th March 1917 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

After being given a month’s leave to recuperate from the non-stop traumas and massive workloads encountered on the Western Front, Douglas of course was kept busy with lighter duties, but no time off. He was examined by General Culling (could this be Surgeon-General John Chislet Culling M.R.C.S., A.M.S., who as recently as January 5th 1917 had been made a Knight of Grace in the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England?) and a Captain Wilson.

“On March 13th I had another Medical Board at Edinburgh Castle, and was passed fit for general service (after my month’s rest!). General Culling and Major Wilson boarded me.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

March 1917

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“I was then sent out to Glencorse Barracks where I relieved Captain Millar DSO MC. There I had to look after the Depot sick, and the small hospital for Veneral Diseases, as well as help with the medical examination of recruits. I lived and messed in the Depot. The mess room was a cosy place, and the regular officers dined at night in their full regimentals – Royal Scots, of course. Capt. the Honourable R Balfour, was one of the Depot officers at that time, and Colonel Wemyss was C.O. I wasn’t overworked and got into Edinburgh by bus a good deal. Here are one or two notes I made about four of the Depot Officers:

Capt. Salmond: A great old chap – uncertain age. Very quiet, but gets very frisky when the Colonel isn’t about. Very conscientious and kind-hearted. A great punster, and fond of a joke.

Lieut. Darragh: a thin poor specimen. Age about 30. Talks about 30 to the dozen and without much sense. Smokes endless cigarettes, is a moral wreck, as well as a physical one.

Lieut. MacDougall: a heavy-weight with about ten double-chins. Said to possess about £12,000 per year. Brays a lot about his knowledge of Court gossip, but is quite harmless. Eats and drinks a lot. His chief hobby is ‘talking’ and he has a wonderful ‘gift of the gab’.

Lieut. Col. Wemyss: a little stout man with a face like a par-boiled lobster. Very fond of a whisky and soda. An old soldier. Not married but fond of the girls. A moody man, and likes to pull one’s leg.”

Douglas was posted to Glencorse Barracks. He tells us of fairly light duties and takes time to describe some of the incumbents there.

Known at the time as Greenlaw Military Prison, Glencorse Barracks at Penicuik were built in 1803. Expanded in 1813 to accommodate up to 6000 French Prisoners of War and the guards to mind them, but following the success of Wellington at Waterloo in 1815, effectively ending the war, the prisoners were returned to France. So the place was largely underused for the next sixty years. In 1875 it was converted to an infantry barracks at the enormous cost of about £30,000.

Over the years it has accumulated something of a dark history. In 1807 Ensign Hugh Maxwell was convicted of the culpable homicide of prisoner Charles Cottier and was given a nine month prison sentence. Much later in 1985, the horrific triple murder of three soldiers based at the barracks was carried out by a corporal following a wage robbery. Corporal Andrew Walker was convicted and given a life sentence with a recommendation he serve a minimum of 30 years reduced on appeal to 27 years. http://murderpedia.org/male.W/w/walker-andrew.htm

Walker suffered a stroke in 2009 and was released in 2011 about a year early on compassionate grounds.

Then in October 2016 Lance Corporal Trimaan Dhillon based at Glencorse was charged with the murder of Alice Ruggles at a flat in Gateshead. http://www.bbcmundo.com/news/uk-england-tyne-37666404

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

27th February 1917 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“I was on duty at the Castle until 27th February, sitting on Medical Boards there, visiting sick soldiers home on leave, or going to such places as Jedburgh, Newcastleton, Winchburgh, etc., to board pensioners.”

This period of the war was a quiet time for Douglas. He was based at home at 22 Alba Street which was within 20 minutes’ walk of the Castle. Douglas refers a few times to “boarding”. This is a reference to what was clearly a military term for medical examinations or appearing before a medical board. The towns that he mentions travelling to were all reachable by train which is the most likely mode of transport that he would have used and he would have been granted an Army railway warrant for travel. It is interesting to note that in 2017 not all these journeys are possible by train because of the Beeching cuts. However there are currently plans for some of these routes to be reinstated.

Douglas refers to boarding pensioners. He doesn’t make this clear but we feel that what he is referring to is examining former service personnel or their dependants who had suffered injury or disability during service and were in receipt of a state pension and not necessarily those older people that were in receipt of an Old Age Pension which was introduced in 1909.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

8th February 1917 Thursday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

After the short time Douglas had been in Perth, he finds himself on the move again, but this time it’s back home.

“On Thursday February the 8th I was ordered back to Edinburgh Castle. I was relieved by a Dr. Jean Gordon and was very sorry to leave Perth. I got a great send off. My pockets were filled with paper and my service hat filled with sugar and salt. Some of the nurses saw me off at the station”.

It seems like this obituary from 1937 is likely to be the very same Dr Jean Gordon.

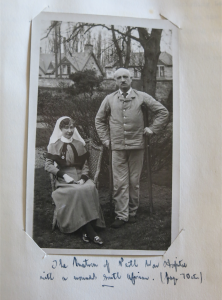

“JEAN GORDON.

Dr. Jean Paton Gordon died on July 13 1937 at her residence, Rannoch Lodge, Claremont, Cape Town, after a long and severe illness.

Dr. Gordon was a daughter of the late Mr. and Mrs. Allan Gordon of Linksfield, Montrose, Scotland. She studied medicine at Edinburgh University, where she graduated as M.B. and Ch.B. before she was 21 years of age. Following her graduation she held various appointments in hospitals, specializing in mental diseases and surgery. Early in 1915, having been refused by the R.A.M.C., she joined the Scottish Women’ Hospital at Troyes. This was a tent hospital of some 200 beds for French soldiers run by the French authorities. Later the R.A.M.C. asked for women doctors and in 1916 Dr. Gordon joined the staff of the Edinburgh War Hospital at Leith.

In 1917 she was attached to the Egyptian Expeditionary Force for service in hospitals at Alexandria and Cairo. She spent two years in Egypt before being demobilised in 1919.

On her return to England she was on the medical staff of the Derbyshire County Council for four years. She joined the Union Mental Hospitals Service in 1923, and was at first stationed at Bloemfontein before being transferred to Grahamstown. Later she joined the staff of the Valkenberg Mental Hospital, where she remained until retiring on pension in 1934.

Dr. Gordon was then able to start a private home of her own for nervous and mental cases, which was most successful.

Her career as a woman doctor has been remarkable and outstanding in view of her unusual skill and her personality, which was felt and loved by all who came in contact with her.

Her greatest pleasure was travelling and she made many trips overseas while practising in South Africa and visited the Continent, Norway and the United States.

The funeral took place at Woltemade No 1 Cemetery. The service was conducted at St. Saviours church, Claremont, by the Rev. le Mesurier, assisted by the Rev. A.J. Lewis.

Dr. Mrs., and Miss Moon and Mr. and Mr. A.B. Reid were the chief mourners. The pall-bearers were Dr. Moon, the Rev. A.J.Lewis, Dr. Forster, Mr. A.B. Reid, Dr. A.J. Ballentine, Dr. Y. Key.

Among those present were: Mr. E.H.Stokesbury, Dr. Botha, Mr. P.R. de Villiers, Mr. R Rigby and J.D. Milne, also staff on Valkenburg Mental Hospital.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

End of January 1917

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

As January drew to a close, Douglas is sent for a medical examination of himself!

“I had a Medical Board at the barracks one day. Drs. Kilpatrick and Graham thoroughly overhauled me and discovered that I was anaemic, had a heart murmur and that I was rheumatic! Rot! They granted me a month’s rest. Good! But I never got it”!

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

6th January 1917 Saturday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

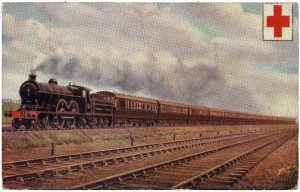

“An ambulance train arrived in Perth Station at 12.30 on the morning of the 6th January. It was a bitterly cold night – freezing hard. The wounded and sick came rolling along to us in ambulance cars and private motors. We admitted 53 cases altogether, and I didn’t get to bed until nearly 5 o’clock. Some of the wounds were very serious, and the men were all very tired.”

Prior to the start of The Great War, Britain had made arrangements to deal with the mass casualties of such an event. Although the concept of the ambulance train owed its origins to the Crimean war of 1854, the main railway companies had been called together and asked to prepare hospital or ambulance trains. Drawings had been sent out for the requirements of such and plans were so well advanced that the first ambulance trains met the hospital ships arriving in Southampton just 20 days after hostilities began.

Men had joined up from all over Great Britain and of course needed to be returned as near to their homes or regimental bases as possible. The trains were made up of everything you would expect to have found in a contemporary hospital. Wards for the casualties, treatment areas and operating theatres. Beds for those that needed them and more casual accommodation for the walking wounded. Accommodation also for the many medical staff on board. Double entrance doors to the carriages to facilitate easy loading. The trains could consist of up to 17 vehicles that could be a third of a mile in length.

Working conditions for medics could be arduous. During difficult times, men with serious injuries by now infected after days of travelling and carrying lice and disease, made life harder for the railway medics than those dealing with it on the front line. Trains could become dirty very quickly working under such pressure. The stench associated with gangrenous infections and trench foot would make the confines stink unbearably. Journey times would be long, progress would be slow as paths for the trains had to be slotted in between regular traffic. Wartime passenger trains, freight trains now heavy with equipment for war, coal trains busier than ever to keep the railways and industry moving, munitions trains and trains full of fresh troops heading for the front to provide more fodder for even more ambulance trains. Long waits for passing prioritised traffic would have been common. It’s not hard to imagine the frustration as progress was halted yet again as the train was reversed into a siding to clear yet another path. Life for the men on the locomotive footplate was hard too with men working extremely long shifts, not knowing when they would arrive or be relieved.

Douglas having experienced life at the front, in the trenches and dressing stations, would be fully aware of what the patients in the Perth War Hospital had gone through. The train that arrived that cold night would have presented him with a scene he was all too familiar with, so was well placed to deal with it, but his understated version of the event almost betrays the chaotic order to which all were subjected to.

Ambulance Train of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway https://www.worldwar1postcards.com/ambulance-trains.php

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here