Monthly Archives: August 2018

31st August 1918, Saturday

Vile tea, a bit of improvised training and then an exciting river chase!

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

There seemed to be no respite for Douglas now. Despite never having borne arms for the last 4 years in the war, he now finds himself brandishing a museum piece of a gun given to him to protect himself. What follows is an exciting episode in itself and an amazing departure from sick parades, blood soaked hospitals and emergency surgeries.

“All next day which was dull and mild we proceeded slowly on our way. The Royal Scots were given rifle and machine-gun practice from the roof of the barge, as very few of them knew how to handle these war-like implements! The Royal Scots struck me as being a poor lot. They were all B category men. Most of them were under-sized, and maldeveloped, and many wore spectacles. Our food consisted of bully beef, biscuits, jam, and vile tea made from Dwina water from the boiler of one of the tugs. It’s a wonder all of us hadn’t diarrhoea after drinking it.

About 4 p.m. that day (August 31st, Saturday) a paddle steamer came rapidly down-stream and hailed us. She had a Russian flying corps lieutenant on board, who had come from Siskoe (our destination) in a great hurry to tell us that the Bolshevik forces, three hundred strong were marching on Siskoe (pronounced S-e-e-s-k). He also told us that a Slavo-British force about sixty strong under Capt. Shevtoff (a Colonel in the old Russian army) was attempting to hold up the Bolshevik advance. After a hurried council of war most of us, including Capt. Scott, Capt. Merchant, Lt. Anderson and myself got on to the paddle-steamer, and steamed “hell for leather” to the relief of Siskoe! A party of a dozen men was left on the barge to guard our stores and baggage, and the small tug detailed to come along with it. The rest of the men were transferred to the second and larger tug, which followed us. Machine-guns were mounted on the deck of our boat, and rifles loaded. The excitement was intense! Capt Merchant lent me an ancient, and cumbersome Spanish revolver captured from the Bolsheviks, and I prepared for the worst. In spite of all the excited Russian officer told us none of us believed the situation to be so bad as he had painted it.

Nothing further happened till about 10 p.m. when a sentry came down to the stuffy little cabin which we occupied to tell us that there was some signalling with a lamp going on behind us. We all trooped up on deck, and there sure enough in the darkness a hundred yards or so behind us was a lamp signalling. As none of us knew the Morse code, we called up two Royal Scot signallers, and they interpreted the message as “stop”. So we stopped, and wondered what was going to happen next. Was it a Bolshevik gun-boat, or what? Soon the boat came into view, and with a sigh of relief we recognised it as a British M.L. After some difficulty she came alongside, and the commander – a young and cheery Lieut. R.N. – came aboard. He informed us that he had left Archangel at noon to-day with instructions to catch us up, and tell us that the Bolsheviks were probably occupying Siskoe – our landing place! He had come up the Dwina at the rate of twenty-two knots an hour. Some speed! He just caught us up in time, for we were then only a few miles from Siskoe. We had another conference, and eventually decided that the M.L. should go on ahead of us and find out if the coast was clear. So we crept slowly along with all lights out. It was a pitch-black night, raw and cold. My Horlochs* lamp was useful in keeping us in touch with the M.L. Eventually we moored alongside the island opposite Siskoe just after 11 o’clock. Capts. Scott and Merchant went ashore to find out what was what, whilst Anderson and I very wisely had forty winks in the stuffy cabin. The adventurers returned about 3 a.m. (September 1st), and told us that the Bolsheviks were about twenty miles away, and that Capt. Shevtoff, and his Russians were in the village of Monastir about five miles off. So far so good. We all went to sleep.”

(Map: Diary)

* Update November 2020. We have discovered via the Great War Forum that Douglas was probably referring to an Orilux lamp and that ‘Horlochs’ was a transcription error in his diary. We have come across other errors like this and believe that the diary may have been dictated to a typist who misheard him.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

30th August 1918 Friday

Scrambling around for supplies for a mission along the Dwina River

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“At 2.50 p.m. on Friday August 30th I received orders from Major Richmond, R.A.M.C. (now Lt. Col.) commanding 85th General Hospital, to report to Capt. Scott. M.C., 2/10th Royal Scots at 3 p.m. on a barge at Bakharitza quay – situation unknown – and to take seven days’ rations with me. That was all. The order came from the A.D.M.S. I reported to Capt. Scott at 3.15 p.m., and found that he was in charge of a small force of some fifty Royal Scots under Lt. Anderson, and forty R.M.L.I. under Capt. Merchant, and that our destination was Siskoe on the Dwina. (Later I discovered that this force was supposed to effect a junction with Col. Haselden (B. Force), who was at that time hemmed in on both sides by Bolsheviks between Obozerskaya and Seletskoe). Lt. Col. Sutherland, 2/10th Royal Scots, who was supervising the embarkation of the force, asked me if I had any medical supplies with me. I replied in the negative as I had not been ordered to bring any. On ascertaining that there were none on board I immediately took steps to procure same, and after some difficulty managed to obtain a Medical Companion, a Surgical Haversack, two water-bottles, and two stretchers from Lt. & Q.M. Warey, R.A.M.C. 85th General Hospital. I had no R.A.M.C. personnel attached to me, although I asked for two men. Moreover there were no trained stretcher-bearers in the party. But I taught two Royal Scots, and two Marines a little first aid on the journey up river.

The barge we occupied was a vile affair. One half of it was under water, with the result that the men had to crowd together in the other half. Moreover there were no heating or cooking arrangements on board, although just before we started we managed to “acquire” a stove of sorts from a neighbouring tug. The tug detailed to pull us up-stream was a miserable little thing of about twelve H.P., and capable of doing about 2 M.P.H. against the stream. We calculated that it would take us about three days to reach our destination. And this was supposed to be an urgent expedition!

We eventually set off about 6.30 p.m. in a thick, damp mist, and not in the best of spirits. About 10 p.m. having proceeded about six miles, we stopped, and got some boiling water from the tug to make tea with. Then another tug came along, also proceeding up-stream, but with nothing in tow. We hailed her, and after a lot of talking (luckily we had an interpreter with us) managed to persuade the new arrival to help us along. I slept that night amongst the men, and was quite comfortable.”

It was a case of thinking on your feet for Douglas. No trained medical men to accompany him he took some likely looking men and quickly trained them in the rudiments of first aid. It was the experiences gained on the Western Front and other theatres of war at the time that saw the rapid development of first aid in the field. It highlighted the importance of getting fast treatment to injured men that would save not only their lives but just as importantly for the army, greatly increase the chances of returning men to the front line.

The Quarter-Master, Lt. Warey, probably spent his peacetime living at 133 Oxford St in central London and was married in Dorset although at the moment this is subject to confirmation. We greatly encourage any further information on Lt.Warey

(Photo: Diary)

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

26th to 28th August 1918 Monday to Wednesday

Voyage to Russia

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

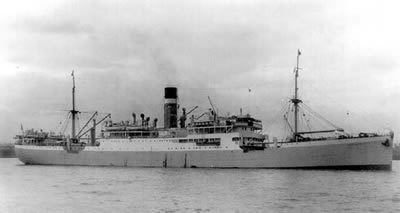

“After a pleasant and uneventful voyage out from Newcastle, England, on the “City of Cairo” I arrived at Archangel on Monday, August 26th 1918, as one of the staff of 85th General Hospital, which was on board the same boat. As no arrangements had been made by the A.D.M.S. – Col. McDermott – for billeting us, we remained on the ship till the 28th August. After some difficulty billets were got for the officers and men in wooden huts at Bakharitza. These billets were in a filthy condition, and swarming with bugs. Russian refugees had previously occupied them.”

City of Cairo in 1915

The S.S. City of Cairo was built in Hull in 1915 for Ellerman Lines. She was to have a chequered career. In 1929 in Liverpool her propeller struck the tug Speedy, sending the tug to the bottom. City of Cairo herself was destroyed at the hands of a German U-boat in 1942, whilst making her way from Cape Town to Brazil. She lay lost in the South Atlantic for 73 years until rediscovered by treasure hunting salvagers. Finding her was one thing but she lay in extremely deep water. At 17,000 feet she was 4,500 feet deeper than Titanic, but the record breaking salvage operation in 2015 resulted in the recovery of £34,000,000 worth of booty which was shared between the British Treasury and the salvage company.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

A Different War: Off to Archangel and more conflict.

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

After being gassed on the Western Front Captain Douglas Page now a seasoned 25 year old war veteran was returned to England via a hospital ship and train. Landing at Southampton from where he had embarked on his incredible journey in November 1915. He was taken to Sommerville College Oxford which had been requisitioned for service as a hospital for officers during the Great War and it was here that he began the slow process of recovery. Unfortunately for us Douglas’s diary entries had stopped during his convalescence, but what we do know is that he did make a full recovery. It is remarkable that not only did it take a month to succumb to the effects of the mouthfuls of gas that he ingested on the morning of the 11th March 1918, but also that it then made him so ill that he was sent home to recover.

When he was well enough to work he went to help the sick and wounded at Chester War Hospital, but by late August he was to be returned to the theatre of war once more. This time though his adventure was to be a different one. He had been signed on to serve another term in November 1917, so in effect Douglas was still under contract when he received orders to return to duty. This time however it wasn’t the Western Front, despite the fact that a further 440,000 were sent there from the start of the Kaiser’s “Spring Offensive” from March until August. Possibly as a surprise twist to his army career Douglas was to be sent to support the British participation of the North Russian Intervention.

Prelude and backdrop to the North Russian Intervention.

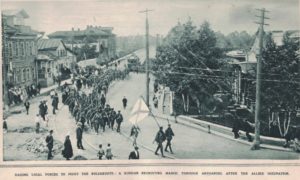

Following the February revolution of 1917 and Russia’s subsequent withdrawal from the War in Europe, civil war erupted in Russia. Britain as a former ally of Tsarist Russia was now part of the group of nations, Britain, USA, Canada, Australia and France that formed the Entente Powers group to intervene in Russia. They together with the White Army would oppose the Bolsheviks who had taken over the Russian government during the further rising of October 1917.

Britain and her allies were anxious to keep Russia in the war despite its formal withdrawal. The Entente Powers had a vested interest for Russia to keep fighting Germany on the Eastern Front. America, having joined the conflict in April 1917 had given support to the Provisional Russian Government, both financial and with materials. However, much of the materials arriving in the northern ports of Archangel and Murmansk had become stuck there.

During the uprising the Russian Provisional Government army known as the White Army had received much support from the Czechoslovak Legion. The Czechs and Slovaks living in Russia at the beginning of the war in 1914 had offered their services to the Imperial Russian government on the understanding that in return Russia would support them in their quest for homeland independence. They had formed an army of about 100,000 men including about 8000 Slovaks and others. By 1917 their purpose was to ultimately gain allied support for independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Unfortunately for the Czechs the Russian White Army was plagued with desertion and mutiny making things much more difficult for the brave and organised Czech Legion. The Entente Powers’ forces were to give the Czechs support against the Bolsheviks.

Following the success of Lenin and the Red Army during October, Lenin had offered safe passage for the Czechs if as neutrals they withdrew from Russia. An orderly withdrawal was to take place via the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok. During the withdrawal an intervention by Trotsky ordered the arrest of the Czechs and the surrender of their arms. The Czechoslovak Legion resisted and fighting broke out in pockets along the Trans-Siberian Railway. By July 1918 the Czechs had taken Vladivostok and controlled the south of the country along the Trans-Siberian. The deposed Tsar Nicolai II and his family had been held prisoners in the southern city of Yekaterina. Lenin then ordered their execution which took place on the 17th July 1918, just days before the Czechs would arrive there which would probably have saved them.

The news of the Czech successes was well received by the allied governments that inspired the joint intervention. However, Britain’s part in the proposed action, although enthusiastically supported by some members of the government like Lord Milner the Secretary of State for War and his successor in 1919 Winston Churchill, it was much less popular with the general population who had suffered four years of war, losing so many loved ones for what seemed like a just cause. This new campaign stretched the loyalties of the British public a bit too far.

UK recruits for the North Russia Expeditionary Force were drawn from members of the Royal Marine Artillery and formed the Royal Marine Light Infantry. Not many of the men were over 19 years old. Hardly any of its officers had seen any action on land and into this were mixed recently released Prisoners of War that were sent straight back into action without being given any leave. America had sent over 5000 men with more to follow along with a smattering of Canadians

As soon as Douglas was to reach Archangel or Arkhangelsk as it was known then, he was plunged into the thick of it. At the beginning of August, the White Army had secured the Archangel area and the allied forces had made advances to the south. The port of Archangel was in the control of several allied ships and the area seemed to be secure. By the 28th the new RALI was ordered to take a village called Koikori, but sustained heavy casualties with 3 killed and 18 wounded. This was obviously something of a morale breaking event for the inexperienced men and when a week later a second attack again failed it only added to their concern. Then when a third attempt was ordered the battalion refused and withdrew to a safer location under the control of friendly villagers. 93 men were court martialled, 13 received the death sentence the rest given hard labour. The sentences were considered too harsh, so when many British MPs objected the government were forced to quash the death sentences and reduce the sentences of the others.

This then was the atmosphere in Northern Russia to which Captain Douglas Page RAMC MC was introduced at the end of August 1918.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here