Ray

27th June 1917 Wednesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“Next day after a busy sick-parade – mostly blistered feet – I walked over to the training area, a distance of about three miles, via Cohem and Enquin-les-Mines. At the latter place I saw a lot of greasy Portuguese troops. At the training area I watched our troops laying out an exact replica of our trench system at Ypres – training for the big push next month! Trenches were being cut through fields of growing corn. It seemed an awful waste.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

26th June 1917 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“On Tuesday 26th June, we marched off to Boncourt, via Rely, Flichet and Tiremade.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

25th June 1917 Monday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“Next day I rode into Aire with Captain Morgan. We did some shopping for the Mess and had lunch at the ‘Chef d’Or’. We saw several battalions of the 15th (Scottish) Division, march through Aire – Camerons, Black Watch &c. It was a great sight, and the sound of the pipes did me good.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

24th June 1917 Sunday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“Up at 5 o’clock next day, and a big sick-parade to attend to, – no wonder, after the Ypres experience. I arranged to have the packs of several of these men carried on a wagon. We left Arcques at 8 a.m. for Morbly – three miles from Aire. It was a long and tiring march, the day being hot and sunny. At Morbly the engineers were billeted in small farms and I had a room in a small cottage. The surrounding country was very pretty, wooded and the gardens were full of fruit and vegetables.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

23rd June 1917 Saturday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

In the sequence of casualty clearing for the injured were main hospitals known as Base Hospitals. These were categorised as either General Hospitals or Stationary Hospitals. The sequence would typically be: stretcher bearers on the field would be the first aid, in many cases men could be left for many hours in the open waiting to be retrieved. Hopefully they would then be taken to the nearest field ambulance before being taken to an Advance Dressing Station, then to a Casualty Clearing Station. From there to an ambulance train or barge they would be taken to a Base Hospital. These would be usually a large building like a hotel or casino and needed to be near a place of repatriation often a seaside resort, port or rail hub.

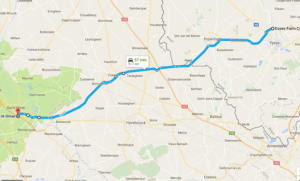

Douglas now found himself on the way to the inland, No. 4 Stationary Hospital in Arques, just east of St.Omer.

“On the 23rd June I joined the 124th Company Royal Engineers as Medical Officer. I went in an ambulance car to Arcques having lunch at St Omer, en route. Arcques was full of troops of the 51st (Scottish) and Irish Divisions. I had dinner that night at No. 4 General Hospital, and collected some stores there. I had a grand sleep at night undisturbed by shells or bombs! – and in a very comfortable billet.”

(Q 28915) Troops attending Divine Service, No. 4, Stationary Hospital, Arques. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205268867

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

18th June 1917 Monday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

There’s never a good time to suffer an air raid, but at half three in the morning it must be particularly harrowing. The sound of an aircraft overhead would be met by thinking is it ours or theirs? It didn’t take long to find the answer.

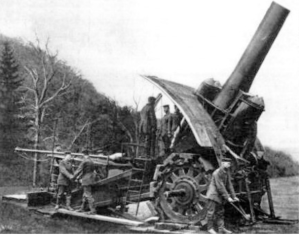

“About 3.30 a.m. on the 18th June a Hun aeroplane flew over very low and dropped ten bombs all around us. The noise of the crashes was terrific and soon we were busy – Capt. Burke and I – attending to a score or more of seriously wounded men – most of them Seaforth Highlanders from a neighbouring camp. We had to amputate one poor fellow’s leg. The Huns enjoyed themselves shelling all the camps around here, with 16″ high velocity shells, nasty things which arrived so quickly that you had no time to seek cover. They fairly scared one! And at night the bombing aeroplanes kept us awake so that our nerves soon got ‘jumpy’. How we escaped I do not know, for shells and bombs dropped all round us by day and by night, causing numerous casualties.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

13th June 1917 Wednesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

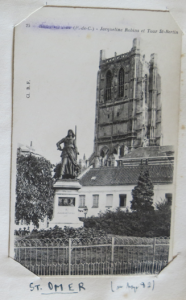

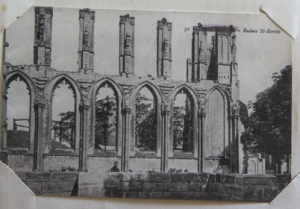

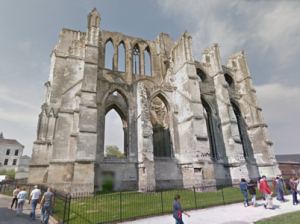

The postcards in Douglas’s diary show the tower and ruins of the Abbey of St. Bertin in St. Omer. The Benedictine Abbey had been first established in the 7th Century and the ruined building dated from the early 1500’s. Following the revolution of 1789 the Abbey was closed and its destruction was ordered by the local commune in 1830. The tower was to remain and a buttress was built to support it and it stood until 1947 when it collapsed due to damage sustained in WW2.

Depicted in the postcard is a statue that stands in front of the Abbey. It was a monument to a woman called Jacqueline Robin, who as legend had it had provided troops defending the town against a siege in 1710 with food and supplies to keep the defenders fit enough to ward off the sieging army. As late as 1936 historians had decided that in fact not only had there been no siege, but supplies for the local army forces were in fact provided by the government. The statue was removed and during the second World War, in 1944 it was scrapped and melted down by the occupying Germans.

“On the 13th June Capt. Burke and I set off in an ambulance car for St Omer. It was a fine run via Abeele, Cassel and Arcques. We saw lots of troops with guns and pontoons on the move. We lunched at the Hotel de France and then did some shopping, and drew a lot of stores from the British Red Cross depot. After tea at the Officers’ Club we had a walk in the beautiful gardens. St Omer was full of Guards and ‘Jocks’.”

Read about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

7th June 1917 Thursday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

Today began the assault on Messines, widely regarded as a military success for the British and their allies, but at the same time some observers felt that its strategic value wasn’t that significant. The German viewpoint seems to confirm that it was a defeat for them, Ludendorff and Hindenburg later wrote of their regrets over Messines. It was a week long battle that did result in some gains and at the time served to improve morale at a much needed moment. It was also to be the precursor of the next “Big Push” by Haig in the next important stage of the war which was to be known as the “Third Battle of Ypres” or by its simpler name “Passchendaele”.

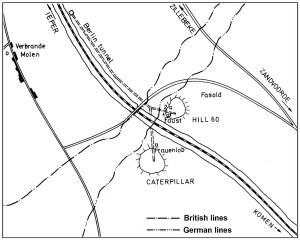

Hill 60 was in fact a pair of hills known before the war as Cote de Amants or Lovers Knoll, the northern of the two was known as Hill 60 and the southern the Caterpillar. British engineers had been tunnelling below Hill 60 for almost two years and had packed the tunnels with many tonnes of high explosives. On this day those explosives were detonated and thousands of German soldiers were blown to bits along with a large chunk of Hill 60.

“At 4 a.m. on 7th June there was a terrific bombardment and later we heard that we had captured Messines and Hill 60 with 9,000 prisoners. All the casualty clearing stations at Poperinghe and Proven were very busy. We were kept busy too attending to wounded and gassed men.”

Image by ViennaUK via Creative Commons https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hill_60_(Ypres)#/media/File:Battle_of_Messines_1917_mine_plan_-_Hill_60.jpg

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

6th June 1917 Wednesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

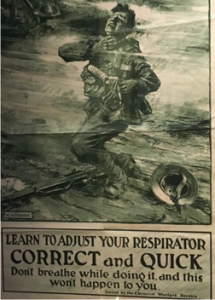

The subject of gas had been very much to the fore of late so not surprisingly it was felt that the allies should respond in kind. The French were the first users of gas, almost from the start in August 1914. Following its use by the Germans, British forces first used gas in September 1915 with pretty disastrous consequences. At the Battle of Loos the wind turned after discharging the gas and blew it back over the British lines causing casualties to our own men. Coupled with the fact that the wrong keys to open the cylinders had been supplied, preventing the full discharge of gas supplies, it could be said, it didn’t go well. None-the-less the use of gas was continued and used by all the main combatants during the conflict.

You can read more on the subject here

“Next day – Wednesday 6th June, the Huns ‘straffed’ the canal bank all day long especially around Bridge 5, so that we were shaken up again badly. One of our men was hit on the head by a piece of shell as he was going from one dug-out to the other. The special gas-officer in charge of the gas brigade paid me a visit, and told me that he has five hundred small guns in White Trench ready ready to fire off one shell each, each shell containing 30lbs of liquid gas which explodes 500 yards behind the enemy lines, and having an enormous concentration, killing immediately. Such is modern warfare! I was relieved at night and proceeded back to Ambulance Headquarters. My heart was in my mouth on the journey back as shells were exploding everywhere. Dead horses and smashed limbers lined the roads.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

5th June 1917 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

The trench system on the Ypres Salient was as in other places a labyrinth of narrow gauge railways that served the troops all over the Western Front. Douglas told us of his meeting Lt. Nesbit of 11th Army Corp Trench Tramways back on New Year’s Day 1916. Canadian forces, along with the French and Australians were largely responsible for the creation and operation of much of the tramway network. Constructed along the lines of the French Decauville* railway system in 600mm gauge, the standard was adopted by all sides including the Germans. It was felt that the Canadians had a great deal of expertise in creating railways in the most extreme conditions and this experience could be put to good use on the Western Front. This also allowed the deployment of older men, railwaymen that normally would have been considered too old for fighting.

“On June 5th the Huns dropped shells all around us from 4.30 p.m. till 10.30 p.m. in an effort to smash up a field gun situated behind our dug-outs. Unfortunately the attempt failed. We would have been really glad to see the gun blown sky-high, for it annoyed us when it fired, and its fire always caused enemy retaliation. We all had the breeze-up pretty badly. When that was over all our big guns had a hurricane bombardment of the Hun front line for 10 minutes. The enemy retaliated and we had a lot of casualties, amongst them being some of the Tramway Company, two being killed and ten wounded. They were all old men – sixty or over. It was pitiful to see such old men being slaughtered like this.”

All Change for the Front!

Off-loading from standard gauge to narrow gauge at the battle of Passchendaele 1917

* Decauville_Portable_Railway_System

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here