9th January 1916 Sunday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

Douglas continued,

“Shortly after midnight a message came through that the Huns were going to attack on our right at 2am Sunday (again) 9th January. We were all told to ‘stand to’ with gas helmets at the alert. Wind up completely! Promptly at 2 o’clock the bombardment began. Our guns replied strongly. Rifle and machinegun fire started also and the noise was terrific. I sat in my aid-post with my orderlies waiting for the worst to happen. Shells were exploding all around making holes in the old house. Bullets were pinging up against the walls behind me. This went on for a solid hour. Strange to say no one was wounded and I got some sleep when all was quiet again. It all started on again at 3 in the afternoon, but this time I had work to do, which kept my mind off the noise outside. One poor man had a piece of shrapnel through the roof of his mouth and into the brain. He didn’t live long. Another man had both his legs smashed to pulp. I had to chloroform him to dress his wounds and control the bleeding. I sent all the wounded off on trolleys to the dressing station at Green Barn where Capt. Ffoulkes was in charge.

All our casualties came from C company on the extreme right, where the Huns were shelling and trench mortaring the ‘Ducks Bill’ (part of our trenches that jutted out into ‘No man’s land’.)

Whilst I was busy attending to my wounded, the A.D.M.S. appeared on the scene and wanted to know why I wasn’t wearing a white surgical gown! Just fancy a surgeon’s gown in a shell-stricken dugout. I felt like hitting him!”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

8th January 1916 Saturday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC. Saturday and it was back into the trenches. It was an eventful evening, as told by Douglas.

Saturday and it was back into the trenches. It was an eventful evening, as told by Douglas.

“It was a fine clear evening with a new moon. At Rougecroix we saw the huge crucifix standing erect and lonely by the roadside, and houses all around smashed to rubbish.

Here we left the road and entered a very fine communication trench. It afforded ample protection from bullets, which we could hear whining overhead. Soon we came to a sunken road and 500 yards along came to Ebenezer Farm, which was Battalion Headquarters. My aid-post was situated in one of the back rooms of the farmhouse only part of which was standing. The officers’ mess and sleeping quarters were in sand-bagged dugouts behind the house. We were here about 500 yards behind the enemy line.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

7th January 1916 Friday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

Ebenezer Farm was an old farmhouse that had suffered a lot of shell damage, but was the site of a dugout command post and served as a front line dressing station. The farmhouse had recently witnessed a remarkable event in history.

On the 15th November 1915 Winston Churchill had resigned from the Government following criticism of his handling of the Dardanelles Campaign. He had joined up with the Scots Guards and taken himself off to the Western Front to try and absolve himself and on the 25th November had been in that very same farmhouse.

Churchill wrote:

“Filth and rubbish everywhere, graves built into the defences and scattered about promiscuously, feet and clothing breaking through the soil, water and muck on all sides; and about this scene in the dazzling moonlight, troops of enormous bats creep and glide, to the unceasing accompaniment of rifles and machine-guns and the venomous whining and whirring of bullets that pass overhead. Amid these surroundings, aided by wet and cold and every minor discomfort, I have found happiness and content such as I have not known for many months”.

Churchill had been summoned that day by the XI Corps Commander to attend the HQ at Merville and told that he was to make his way to the cross roads at Rougecroix to be picked up by a staff motor car. No car appeared and after being advised by an officer that the meeting had been cancelled, Churchill angrily trudged the long walk back through the mud and rain in the dark to arrive back at the farmhouse. When he arrived he discovered that the dugout that he had been sitting in had been hit by a shell only fifteen minutes after he had left which had killed an orderly. That mis-sent telegram order unwittingly changed the history of the world.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

3rd January 1916 Monday to 6th January 1916 Thursday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

The week was to be a relatively quiet one though nonetheless busy for Douglas Page and his men. The ADMS (Assistant Director Medical Services) paid a visit. Meetings were held involving senior officers and discussions had taken place about moving the various sections to new positions. At 9am on Monday morning Captain Anderson marched his ‘C’ company of sixty men and three officers out to attach themselves to 57th Field Ambulance for instructional purposes for a week.

Sick men continued to arrive to be treated, both officers and men. Equipment came and went. Motor transports and horse drawn wagons splashing their iron tyred wheels over the wet ground, meant the camp would have always sounded noisy with the constant clatter of wagons coming and going. Fit men kept busy with camp duties. The many horses, some ailing, would have needed as much attention as the sick men. The sound of blacksmiths’ hammers would have added to the din as farriers re-shod horses. One duty was to follow marching men with a horse-drawn ambulance to pick up stragglers and during the week two groups were detailed to carry out this task.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

2nd January 1916 Sunday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

After only two days at the Advanced Dressing Station (ADS) Douglas and his men were relieved and he marched his fourteen men back to Vieille Chapelle and then back to Calonne where they received a tremendous reception from the rest of the Ambulance. None of Douglas’s men had been injured and to march back with an un-depleted complement was seen as a great achievement.

The celebrations for our man were over quickly though, as almost immediately he was ordered to report to Robecq where there was a hospital for officers, to act as relief Medical Officer (MO) for the 13th Battalion Welsh Regiment. He was to relieve Lt. Elliot who had been sent earlier to act as MO but had himself been taken ill. Arriving by motor ambulance he was well received by the Colonel and Major D’Arcy Edwardes. For the next few days, Lieutenant Page instructed stretcher-bearers and conducted sick parades. Other duties would include censoring the men’s mail and even getting instruction on riding a horse.

Major Edwardes was born into the family of one of Britain’s most famous entertainment gurus of the day. He was the son of a famous musical comedy impresario, George Edwardes. At the age of only twenty, D’Arcy’s father was managing theatres for Richard D’Oyly Carte who founded the Savoy Hotel in London’s Strand. He became the manager of the Gaiety Theatre and other nearby theatres at the same time, introducing popular shows such as A Gaiety Girl.

A familiar character around London’s theatres in the Strand he helped establish the Edwardian Musical Comedy genre of entertainment. You can read more about him here: http://www.musicalcomedysociety.co.uk/home/history

Son George D’Arcy Edwardes (originally without the last ‘e’) had joined up as a regular soldier in 1907 and having returned from India and South Africa was sent to the Western Front in November 1914 and promoted to Captain in 1915. He was promoted to “Temporary” Major later in 1915, this was a way the army could promote people giving senior rank and privileges without having to pay the full wage of the senior rank. He was killed commanding his unit on July 10th 1916 at Memetz in the Somme and his obituary appeared in The Times* thus:

“MAJOR D’ARCY EDWARDES, who was reported missing, believed killed, during July, and subsequently killed, was the only son of the late George Edwardes, the theatrical manager. He was educated at Eton and Sandhurst, and was gazetted to the 1st Royal Dragoons in 1907. He served with his regiment in India and South Africa, returned home in 1914, and went straight to the front. He was promoted captain in 1915, and soon after was transferred and was made temporary major and second in command of a battalion of the Welsh Regiment, which he was commanding at the time of his death.”

* The Times 11th August 1916: pg. 11; Issue 41243

Copyright The War Graves Photographic Project

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

1st January 1916 Saturday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

Douglas woke up that morning after feeling a bit depressed and self-pitiful the night before.

He met with a gravedigger that told him that they dug the graves only three feet deep and buried the dead men either sewn into a canvas shroud or in a blanket.

Douglas wrote:

“The Hun strafed Windy Corner* all morning with ‘Crumps’, shells which made a noise like Ker-r-rump when they exploded. Coal Boxes were another species of shell that produced a large cloud of black smoke. Pip Squeaks and Whizz-Bangs were other shells, the latter arrive very speedily, hence the Whizz-Bang!”

Then he ran into Lt. Nesbit who was in charge of the Trench Tramway system that supplied food, ammunition, wire and equipment up to the trenches and gun emplacements on the front line.

Douglas wrote: “I met with our Lt. Nesbit who was in charge of the 11th Army Corp Trench Tramways. He was badly wounded at Neuve Chapelle (close to us here). He took me to see his abode, a wonder series of dugouts. In his sitting room he had an easy chair or two, a roll top desk, several plain chairs, carpets, marble fireplace and real windows. Pictures adorned the walls and a real bed, a chest of drawers and a large looking glass helped to furnish his bedroom. All these extras he ‘acquired’ from the house of a German spy who was caught and shot in Richebourg not so very long ago”.

The tramway was a narrow gauge line with a system of push trolleys that were also used to ferry the dead and wounded back behind the line. Nesbit’s tramway was known locally as “The Midland” and the stop-off places were all named after well known British railway stations.

Following the meeting with Nesbit, Douglas came face to face with his first taste of death on active service. A young man shot to pieces with machine gun bullets was brought in. It was a hopeless case and Douglas doped him heavily with morphine and the poor young man passed away peacefully no longer in pain.

They buried him in the small cemetery nearby.

This was quickly followed by another type of injury sadly to prove by no means uncommon. A young soldier was brought in with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to his foot. Douglas wrote, “I felt sorry for the poor fellow, no doubt the terrible strain had told on him. He was sent back under escort”. No doubt to face further sanction. “Shooting yourself in the foot” or “taking one for Blighty” became a way that men unable to stand the terrible strain of the conditions of war might inflict on themselves as a way of being sent home.

During WW2 my own father suffered a wound to his foot in which he lost one and a half toes. One day feeling a little brave I asked him about it, trying to get to the truth. “Bloody cheek”! He replied angrily. A piece of shell that had exploded nearby had flown at him and taken the end of his boot off, “Lucky I wasn’t killed!”, he said. It was the end of his war anyway as his whole section had run out of ammunition, they were all captured and carted off to a prisoner of war camp in Munich. A story for another day.

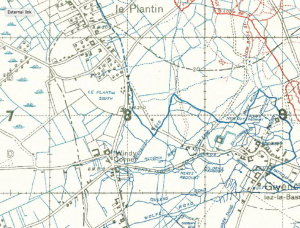

*Maps showing the location of Windy Corner

The next diary entry will follow tomorrow, 2 January.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

31st December 1915 Friday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

So far Douglas had seen his war mainly from the periphery, the sound of gunfire and shelling was more or less constant. Except for the odd incident that almost killed him it was mostly somewhat distant. The effects of war were all too evident with villages and houses badly damaged, trees and vegetation stripped bare and the landscape pockmarked with shell holes. Largely his unit had watched from the distance and treated more sick than wounded. Today however, was the day young Douglas really discovered the war first hand on his first visit to the trenches. His group, himself and fourteen men went forward to the advanced dressing station.

For the first time Douglas arrives in the trenches, they went via Windy Corner and through a long communication trench. He described the wooden boarded trench as “duck-boards” above the knee in water. Apart from shelling a Hun aeroplane that had “ventured up” the evening passed quite peacefully and his first taste of life in the trenches was uneventful.

Here, rather surprisingly perhaps, they ate a roast dinner that sounded as good as you are ever likely to get in a cold wet muddy ditch. Still Douglas didn’t complain and describes the menu in some detail.

“That night five of us, Captains Owen and Smally R.A.M.C.; Lieutenant’s Rt. Johnson and Nesbit and myself, sat down in our little sandbag dugout, to a Hogmanay feast. In spite of our proximity to the front line, we indulged in roast chicken, potatoes and peas; plum pudding and apricots; coffee; biscuits; sweets; cigars; champagne; vin rouge and cherry brandy”

At 11.55 pm he went outside into the crisp starry night, almost silent except for one lone rifle shot. Midnight, brought in the New Year and the men linked arms as they sang Auld Lang Syne, before they returned to the trench.

“At midnight we solemnly toasted the New Year, in the distance we could hear the cheers and the singing of Auld Lang Syne, I felt quite lonely and depressed, but not for long for all of a sudden one of our batteries let off a salvo which the Hun immediately replied to by sending over 11 shells 10 of which didn’t go off (didn’t explode!). In a few minutes all was quiet on the Western Front. I slept on a stretcher in a small dugout. I was very cosy inside my sleeping bag.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

28th December 1915 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

He doesn’t state the exact day but around this time, just saying “one day” Douglas and Captain M. Ffoulkes decided to walk along to Richebourg. A few hundred yards from the village they realised that enemy gunfire was concentrated there. They stopped for around half an hour to observe what was their first experience of seeing real shellfire. They watched as shells burst showering brick and shrapnel everywhere and high explosives pounding the stricken village. Douglas tells the story best, he wrote:

“After the shelling had stopped, Ffoulkes and I decided to venture into the village to investigate things. What a mess! Most of the houses had been reduced to mere heaps of rubble and the church had only half a wall left standing. Curiously the crucifix remained erect. The road in front of the church was in an awful mess being pitted with huge shell holes and littered with brick and stones. We met an Artillery Colonel who told us that he had an observation officer in the church tower in the morning , but that he had got safely away when the bombardment started. The churchyard was a sight, graves torn open and bones and broken headstones lying *pell-mell.”

“While we were inspecting the church a ‘shriek’ came from the east, a Hun shelling coming. I put my hands over my head and ducked. Wind up properly! A tremendous explosion took place 20 yards behind me just behind the wall of the church. What seemed to me like tons of shrapnel and broken bricks came showering down all around. When all had subsided I looked up to see Ffoulkes and the gallant Colonel scuttling down the street like hares. The Colonel was just disappearing round the corner and Ffoulkes was yelling to me to ‘Come on’. I did so without thinking twice about it and ran as I never did before, for I never knew when or where the next shell would burst. However, nothing more happened and we got out of the place safely though a bit shaky after our baptism (so sudden and unexpected) of fire.”

* I was amused by Douglas’s use of the term “pell mell” as it’s not a term we hear in common use today. “Pell Mell” or “Pelle Melle” was a game popular in the 17th century probably originating in Italy. It was played with a curiously shaped mallet, the hammer part having curved upwards faces to give lift to a small wooden ball around the size of a cannon ball. The ball was meant to be hit though a hoop that was suspended from a pole. It was played by gentry in London often in a place that is remembered today as the street Pall Mall.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

26th December 1915 Sunday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

The Diary states that he left Glomenghem with B Section, but maybe he meant to write Calonne instead as he was there until late on the evening of the 25th. He left with B section at 9am under Captain M. Ffoulkes for the Vieille Chapelle battle area and remained there until 30th December.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

25th December 1915 Saturday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

Having just recovered from three days in bed with flu, Douglas attended the packed parish church in Calonne. Douglas was a regular churchgoer throughout his life and sometimes complained that so few of his men attended church services.

He described the church as “a beautiful building, being not unlike St John’s Episcopal Church in Edinburgh”. (The Church of St John the Evangelist was and still is about three minutes’ walk from his parents’ house in Alva St).

Then he continued, “The church was profusely lit by candles, especially up at the altar and there was a tableau at the end of one of the side aisles representing the shepherds with their flocks. The church was packed and there were very few men present. The front pews were occupied by children, who were kept in order by a man in an ancient uniform and cocked hat who carried a gold-topped stick. At times he walked round and administered a resounding smack on the head to some unfortunate child for looking round or not sitting still! It was very comical”.

“The Abbé entered the church accompanied by six little boys in red and white surplices. There was a great jingling of little bells and loud moans from an ancient precentor who had a voice like the Inchkeith foghorn on a particularly foggy night. A choir of girls on the left took up the refrain and the old man and the girls took it in turns to keep up the moan for fully fifteen minutes, until they at last got tired of it. The Curé entered then to the accompaniment of more bells and preached a very fine sermon. He had a splendid voice and spoke very slowly, so that I was able to understand most of what he said. After that there was more moaning from the choir and then the Abbé departed, preceded by his six little attendants and accompanied by bells”.

Christmas Dinner was served up at 8pm. Fourteen of the company sat down to dinner that Christmas night in battle torn northern France, the menu had been devised by their Roman Catholic Padré, Father Brown. Here is that very menu, signed by all of those present.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here