26th to 28th August 1918 Monday to Wednesday

Voyage to Russia

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

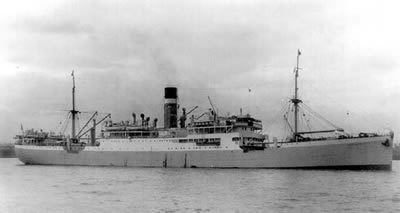

“After a pleasant and uneventful voyage out from Newcastle, England, on the “City of Cairo” I arrived at Archangel on Monday, August 26th 1918, as one of the staff of 85th General Hospital, which was on board the same boat. As no arrangements had been made by the A.D.M.S. – Col. McDermott – for billeting us, we remained on the ship till the 28th August. After some difficulty billets were got for the officers and men in wooden huts at Bakharitza. These billets were in a filthy condition, and swarming with bugs. Russian refugees had previously occupied them.”

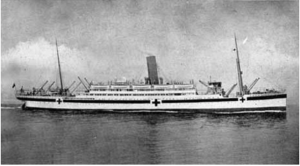

City of Cairo in 1915

The S.S. City of Cairo was built in Hull in 1915 for Ellerman Lines. She was to have a chequered career. In 1929 in Liverpool her propeller struck the tug Speedy, sending the tug to the bottom. City of Cairo herself was destroyed at the hands of a German U-boat in 1942, whilst making her way from Cape Town to Brazil. She lay lost in the South Atlantic for 73 years until rediscovered by treasure hunting salvagers. Finding her was one thing but she lay in extremely deep water. At 17,000 feet she was 4,500 feet deeper than Titanic, but the record breaking salvage operation in 2015 resulted in the recovery of £34,000,000 worth of booty which was shared between the British Treasury and the salvage company.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

A Different War: Off to Archangel and more conflict.

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

After being gassed on the Western Front Captain Douglas Page now a seasoned 25 year old war veteran was returned to England via a hospital ship and train. Landing at Southampton from where he had embarked on his incredible journey in November 1915. He was taken to Sommerville College Oxford which had been requisitioned for service as a hospital for officers during the Great War and it was here that he began the slow process of recovery. Unfortunately for us Douglas’s diary entries had stopped during his convalescence, but what we do know is that he did make a full recovery. It is remarkable that not only did it take a month to succumb to the effects of the mouthfuls of gas that he ingested on the morning of the 11th March 1918, but also that it then made him so ill that he was sent home to recover.

When he was well enough to work he went to help the sick and wounded at Chester War Hospital, but by late August he was to be returned to the theatre of war once more. This time though his adventure was to be a different one. He had been signed on to serve another term in November 1917, so in effect Douglas was still under contract when he received orders to return to duty. This time however it wasn’t the Western Front, despite the fact that a further 440,000 were sent there from the start of the Kaiser’s “Spring Offensive” from March until August. Possibly as a surprise twist to his army career Douglas was to be sent to support the British participation of the North Russian Intervention.

Prelude and backdrop to the North Russian Intervention.

Following the February revolution of 1917 and Russia’s subsequent withdrawal from the War in Europe, civil war erupted in Russia. Britain as a former ally of Tsarist Russia was now part of the group of nations, Britain, USA, Canada, Australia and France that formed the Entente Powers group to intervene in Russia. They together with the White Army would oppose the Bolsheviks who had taken over the Russian government during the further rising of October 1917.

Britain and her allies were anxious to keep Russia in the war despite its formal withdrawal. The Entente Powers had a vested interest for Russia to keep fighting Germany on the Eastern Front. America, having joined the conflict in April 1917 had given support to the Provisional Russian Government, both financial and with materials. However, much of the materials arriving in the northern ports of Archangel and Murmansk had become stuck there.

During the uprising the Russian Provisional Government army known as the White Army had received much support from the Czechoslovak Legion. The Czechs and Slovaks living in Russia at the beginning of the war in 1914 had offered their services to the Imperial Russian government on the understanding that in return Russia would support them in their quest for homeland independence. They had formed an army of about 100,000 men including about 8000 Slovaks and others. By 1917 their purpose was to ultimately gain allied support for independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Unfortunately for the Czechs the Russian White Army was plagued with desertion and mutiny making things much more difficult for the brave and organised Czech Legion. The Entente Powers’ forces were to give the Czechs support against the Bolsheviks.

Following the success of Lenin and the Red Army during October, Lenin had offered safe passage for the Czechs if as neutrals they withdrew from Russia. An orderly withdrawal was to take place via the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok. During the withdrawal an intervention by Trotsky ordered the arrest of the Czechs and the surrender of their arms. The Czechoslovak Legion resisted and fighting broke out in pockets along the Trans-Siberian Railway. By July 1918 the Czechs had taken Vladivostok and controlled the south of the country along the Trans-Siberian. The deposed Tsar Nicolai II and his family had been held prisoners in the southern city of Yekaterina. Lenin then ordered their execution which took place on the 17th July 1918, just days before the Czechs would arrive there which would probably have saved them.

The news of the Czech successes was well received by the allied governments that inspired the joint intervention. However, Britain’s part in the proposed action, although enthusiastically supported by some members of the government like Lord Milner the Secretary of State for War and his successor in 1919 Winston Churchill, it was much less popular with the general population who had suffered four years of war, losing so many loved ones for what seemed like a just cause. This new campaign stretched the loyalties of the British public a bit too far.

UK recruits for the North Russia Expeditionary Force were drawn from members of the Royal Marine Artillery and formed the Royal Marine Light Infantry. Not many of the men were over 19 years old. Hardly any of its officers had seen any action on land and into this were mixed recently released Prisoners of War that were sent straight back into action without being given any leave. America had sent over 5000 men with more to follow along with a smattering of Canadians

As soon as Douglas was to reach Archangel or Arkhangelsk as it was known then, he was plunged into the thick of it. At the beginning of August, the White Army had secured the Archangel area and the allied forces had made advances to the south. The port of Archangel was in the control of several allied ships and the area seemed to be secure. By the 28th the new RALI was ordered to take a village called Koikori, but sustained heavy casualties with 3 killed and 18 wounded. This was obviously something of a morale breaking event for the inexperienced men and when a week later a second attack again failed it only added to their concern. Then when a third attempt was ordered the battalion refused and withdrew to a safer location under the control of friendly villagers. 93 men were court martialled, 13 received the death sentence the rest given hard labour. The sentences were considered too harsh, so when many British MPs objected the government were forced to quash the death sentences and reduce the sentences of the others.

This then was the atmosphere in Northern Russia to which Captain Douglas Page RAMC MC was introduced at the end of August 1918.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

3rd May to 4th May 1918 Friday and Saturday

Blighty bound!

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“About 1am on Friday, May 3rd, I left hospital at Rouen, by ambulance car for Blighty, feeling wonderfully happy in spite of the early hour of departure. We were motored to the Docks Station where we boarded No. 9 ambulance train. There were six of us in a compartment – myself (a Scot), an American doctor, a Lancashire lad, an Irishman, a Yorkshire lad and an officer from the Naval Division. I slept most of the night. We got to Havre at 7 o’clock, and had breakfast and lunch on the train. At 2 p.m. we went aboard the hospital ship ‘Essiquibo’ – a fine boat, only 3 years old, with seven water-tight compartments. I got a lovely little cabin all to myself, and was most comfortable. After an excellent dinner in the gorgeous saloon, we had lifeboat drill, and then a sing-song which delighted the ship’s officers. I slept peacefully all night, and woke up to find our good ship berthed in Southampton. We were disembarked at 10 o’clock and transferred to an ambulance train, which was soon speeding on its way across beautiful England to Oxford. On arrival there we were driven in private cars to our hospital in Somerville College – a beautiful spot. So ended my adventures in France and Flanders.”

HMHS Essequibo was built in 1915 and had been leased to Canada that used her to repatriate men home to Canada. During such a run near the coast of Ireland she was intercepted by a German U-boat that fired a couple of warning shots to stop her. The Germans having ascertained that she was indeed a hospital ship, Essequibo was allowed to continue her journey. She survived the war and was sold to the Pacific Steam Navigation Company in 1922.

After the two day journey and motor transfer to the hospital at Somerville College, Douglas became a patient at the hospital where he spent some time recuperating, before transferring to the War Hospital in Chester. At the moment we have no dates for these events but will add them when we find out.

Douglas ended the first volume of his diary here and makes no mention of his time in Chester but did have a photograph that we include here.

A typical group of wounded soldiers with nursing staff, myself in centre. Taken at Chester War Hospital in 1918.

The first volume of the War Diary of Doctor Douglas C. M. Page M.C. ends here, but there will be some intermediate entries and additions between now and August and the beginning of Volume 2. Hopefully we will have more information on what happened between arriving in Oxford and finding himself aboard yet another ship, bound this time not for the Western Front, but Northern Russia and Archangel. Please join us on that ship in the Autumn to discover the incredible adventures of a remarkable man as his war continues.

At this point it is pertinent to remember another remarkable man. Douglas’s son Gordon Page who sent a copy of this diary to his niece Elizabeth Coggin and so to share Douglas’s adventure with us and now with the world. Gordon passed away very recently and will be sorely missed by his family and friends. He is survived by his wife Ruth, sons Brian and Matthew and daughter Belinda. Brian has also provided us with decent copies of the pictures in the diary for which I am very grateful.

It is a great pleasure to dedicate this work to Gordon Page.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

17th April to 2nd May 1918 Wednesday to Thursday

The Road to Recovery

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“I was in bed for ten days, and the condition of my throat gradually got better. I was extremely well cared for. When I did get up I was very shaky, but was glad to get out into the beautiful gardens of the hospital (a theological college in peace time). When I was able I got out into the town, and saw the lovely cathedral, and the shops. In the mornings I used to help Major Austin in the wards by giving chloroform whilst he dressed the seriously wounded officers.

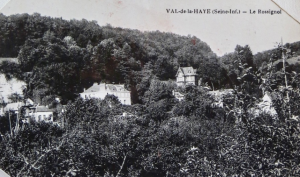

One afternoon another officer and I went for a trip up the river on one of the small steam-boats. It was a beautifully warm and sunny day, and we enjoyed our outing very much. We got off the boat at a pretty little place called Val de Haye, and after a stroll through the village had tea at a place run by an Englishman. There was a merry party of nurses and V.A.D.s on board, and we sang all the way back to Rouen.

Another day we journeyed up river to La Bouille, also a very pretty little village, where we had coffee and biscuits in a quaint old inn.”

By now we know Douglas Page to be a master of the understatement. His narrow escapes that can only pay allegiance to Lady Luck seemed to be never more than a nasty nuisance, responsible for the occasional “wind up”! However, although not deserting him entirely, luck had now worn a bit thin and for the time being at least removed him from the front line of war. The contrast must have been tremendous. Often never more than a few feet or a split second away from being blown to kingdom come, this painful time in hospital at least gave some time to enjoy the nicer side of France.

La Bouille, a little further downstream today retains its rural charm and a convenient car ferry to cross the river.

The No.2 British Red Cross Hospital, Rouen, France. The red cross denotes the ward where Captain Page was a patient.

If Douglas were able to take that same trip now one hundred years later he would be totally shocked at the transformation of the idyllic scene he enjoyed then. Today both banks of the river are lined with the infrastructure of heavy industry. Many wharves flanked by gas and oil tanks, silos, and factories, railway tracks with marshalling yards mark France’s modern prosperity.

A ward in the No.2 British Red Cross Hospital, Rouen, a former theological college. Major Austin (the surgeon) standing in the centre of the ward.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

12th to 16th April 1918 Friday to Tuesday

A Cold Sponge Down by a Middle Aged Nurse!

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“On Friday 12th we packed up, and marched via Talmas to Rubumpre. We pitched our tents in a field outside the village, and had a splendid view of the surrounding country.

I hadn’t felt at all well for some time – not since getting a whiff of gas whilst with the Artillery – and at night on the 13th April felt very seedy. Next day my throat and chest were very painful. My temperature was above normal, and I felt decidedly rotten. As we were to move on again that day, the Colonel very reluctantly decided to send me back to the Casualty Clearing Station at Gezaincourt. So I was packed off there in an ambulance car feeling very miserable, and grieved at having to leave all my good friends. I was a patient in No. 45 C.C.S. for one night only, being evacuated by ambulance train at 8.30 p.m. on the 15th. It was a terribly slow journey – we didn’t reach Rouen until 3 p.m. on the 16th April! However, it was a beautifully equipped and most comfortable train. I was a stretcher case and felt very ill. My throat was completely closed up, and very painful. The doctor in charge of the train was a Captain Cowans, whom I knew as a resident house surgeon with Mr Cathcart in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. At Rouen we were conveyed by motor ambulance to No. 2 British Red Cross Hospital, and after a lot of lying about on my stretcher in vestibules and corridors, I was at length heaved into bed between lovely cool sheets, and felt some better and happier after a cold sponge down by a dear of a Scottish sister (middle-aged!). The doctor – Major Hudson – came to see me in my little room, and told me that my throat and air passages were very badly ulcerated, and must have been so for some considerable time. I was unable to speak or swallow. He prescribed gargles, inhalations and compresses externally. I didn’t sleep – hadn’t had a wink for days now.”

It seems that Douglas had now succumbed to the “mouthfuls” of gas from the attack on March 11th. From the slightly embarrassed mention of the “cold sponge down” it would seem that he was suffering from the effects of mustard gas poisoning. This would often manifest with blistering of the body as well as the ulceration of the throat and respiratory organs. (More on the use and effect of gas in an additional post).

The slow train journey to Rouen was to mark the end of Douglas’s adventures on the Western Front but not the end of his war. That was over a year away.

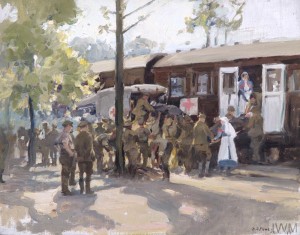

A Red Cross Train, France; wounded British soldiers are transferred from a motor ambulance to a Red Cross train, 1918, artist Harold Septimus Power. (Art.IWM ART 1031) image: Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/22039

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

10th April 1918 Wednesday

Depressing news from the north

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“On the 10th April we heard of the Hun attack ‘up North’ where he has captured the Messine Ridge, Armentiers, Laventie, Fleurbaix, Sailly, Bac St Maur, etc. The ‘Pork and Beans’ (Portuguese) bolted without firing a shot, and let the enemy through. For two hours this evening a continuous cavalcade of our cavalry went through our village on the way north to stem the attack. It was a wonderful sight. They are making a forced march all night, and have to be in in Merville by 8 a.m. tomorrow.”

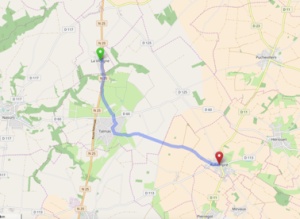

The Long March North to Merville.

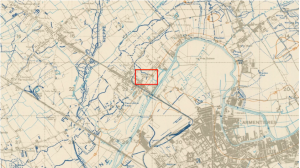

We don’t know where the march began but there was a crippling 82 kms to go to reach Merville by the morning.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

1st and 2nd April 1918 Monday and Tuesday

No Fooling Today, Instead a Difficult Train Journey

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

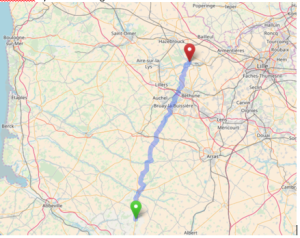

“On Monday, 1st April, we marched to Calonne where we entrained. It was hard work getting the horses on board. The train left at 12.10 a.m. on 2nd April, and we were in the train until noon. We detrained at Doullens, very dirty, tired and hungry.

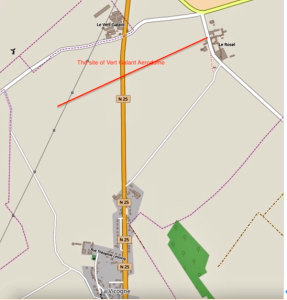

However, we got no respite until we had marched 8 miles along the main Doullens-Amiens road to a little village named La Vicogne. Our men were under canvas in a field, whilst the officers slept on the floor of a room of a big farmhouse. There was a large aerodrome near us. The road was very busy with transport of all kinds.

We were now in the 5th Corps with the 2nd, 12, 17th, 47th, 63rd and 1st New Zealand Divisions, and are in 3rd Army reserve.”

Douglas so far, hadn’t mentioned his recent inhalation of gas received during the attack on the 11th March. Three weeks had passed, but typically for him he makes no mention of it, although it must have been troubling him. A few mouthfuls would not have exactly gone unnoticed.

The work of a Captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps had proved difficult enough but also varied in his duties. Instead of attending to the sick and wounded, it was now necessary to help load reluctant horses into a train and commence another slow journey south. Today this 68 kilometre journey is no longer possible by train.

Douglas and the men he looked after were ordered south to Doullens as part of the effort of attempting to plug the gap caused by the breakthrough of German forces following the start of Operation Michael (The first part of the Kaiser’s Spring Offensive) on the 21st March. Sixteen divisions of the British army were now faced by fifty eight German divisions. Many of them battle hardened, but had had some rest time after withdrawal from the east. They had spent time training in their occupied lands behind the front line since their arrival.

The nearby large aerodrome was Vert Galant. It had been gradually expanding since being established in 1915 with the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Navy Air Service, eventually with the Royal Air Force. It operated until 1919.

The Book by Michael O’Connor “In the Footsteps of the Red Baron” gives the very interesting and full history of Vert Galant.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

30th and 31st March 1918 Saturday and Sunday

Relief and a trek back to Merville

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“Next day I handed over to the 102nd Field Ambulance (34th Division), and got back to L’Estrade in the early afternoon after some hustle.

Next day (Sunday 31st March) we were up early, and marched off to Merville, via Crois du Bac and Estaires. I rode most of the way, and the men marched very well in spite of being tired after so much hustling during the last few days. In Merville the men were billeted in deserted houses and we had our mess and billets in a large empty villa. Most of the houses near the railway station were badly damaged by shells and bombs, and the inhabitants had left the town hurriedly.”

Merville had at this time suffered a great deal of damage and had been almost totally destroyed, its inhabitants had largely gone. Back in November 1915 it was the area HQ for the British Army and was where Churchill had been asked to attend the aborted meeting in the incident that inadvertently saved his life.

Photo © Ray Coggin. The War memorial in Merville, damaged in a subsequent Battle of the Lys in May 1940

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

29th March 1918 Friday

A Hurried Breakfast and Scots From The Somme

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“I took over the Dressing Station at Erquinghem from the 131st Field Ambulance camp on the morning of the 29th, having got sudden orders at 8.35 a.m. to do so. It was some rush. I had a very hurried apology of a breakfast at 8.30, and nothing more till I had a ‘high’ tea at 4.30 p.m.

The 9th Royal Scots (Dandy Ninth), and Macrae’s Battalion came into the village at night. It was fine to see them again. They have just come north from Albert.”

“High Tea” was probably a hot meal and not a plate of scones and sandwiches with the crusts removed.

“The Dandy Ninth”, so called because their uniforms based on the Hunting Stewart tartan, set them apart from other battalions of the Royal Scots. Arriving in France in February 1915 they had earned a reputation for fighting valour having been involved at High Wood on the Somme in 1916 then in 1917 at Arras and Vimy Ridge and later at Passchendaele and Cambrai.

Having come north from Albert, on the Somme where the Germans initially broke through with great success, they would go on to be instrumental in the disruption and later halting of the German advance during the Spring Offensive.

Once the Germans had been halted it was the tipping point of the war and ultimately led to the Armistice.

McCrae’s Battalion was one of Lord Kitchener’s New Army, Pal’s battalions, raised in 1914. Known as the Sportsman’s battalion it recruited predominately from professional sportsmen that included many footballers, drawn from the main clubs in Scotland.

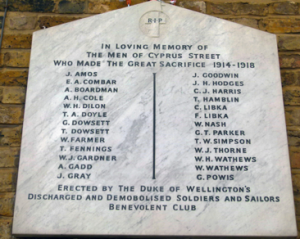

The whole ethos of Pal’s battalions was that men would fight alongside men they knew from private life, encouraging a stronger sense of unity resulting in men watching out for each other and becoming a more determined fighting unit. In reality what happened was in many instances whole families and friends were casualties, causing in many cases almost the entire male population of some areas to be practically annihilated.

One such area was Cyprus St in London’s East End. No less than 26 young men, all from the same street gave their lives for their country. Following the decimation at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 the experiment of Pal’s brigades was discontinued.

You can read more about the 9th Royal Scots here.

You can read more about the McCrae’s Battalion here.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

25th March 1918 Monday

The Pressure On The Allies Was Mounting

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“On the 25th I left Houplines in charge of a sergeant and a squad of men, and went back to Pont de Nieppe Dressing Station. Father Brown paid me a visit, and gave me some news of the doings in the south. He said that the situation was very grave, and was most depressing. He told me that our 113th Brigade leave to-night and that the Australians, Labour Corps and the 12th Division have already left for the battle area, so that we have nobody in reserve behind us now. Let’s hope the Hun doesn’t attack here! Father Brown also told me that the Germans had cavalry in action, and that Paris was being shelled by a long-range 9” gun.”

Pont de Nieppe on the 1918 map. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Modern day map showing Pont de Nieppe. © OpenStreetMap contributors. https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright

It didn’t take long for news to filter through about the start of “Operation Michael” or the Kaiser’s spring offensive. The 113th RWF being deployed quickly to the area near the Somme had left the Armentieres area short of defensive cover at a time that was to prove very challenging for the allied armies.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here