22nd July 1917 Sunday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“On Sunday 22nd, there was a most impressive church parade in a clearing in the road. It was conducted by Capt. Howard, and the 115th Brigade Band led the praise. At night there was a gas alarm, and several enemy aeroplanes flew over, and dropped bombs.

The gorgeous weather – great heat and glorious sunshine – continued all this time, and the ground was dry, which was in favour for the Great Push which we knew would come shortly.”

Douglas mentions “the gorgeous weather” that they were enjoying. The dry ground would have been the kind of conditions that Haig and his Generals were hoping for while planning for the Big Push. The thing was, would it hold out?

Church Parade of the 12th Battalion, King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment 1917. Unknown location. http://www.kingsownmuseum.com/ko2046-23.htm

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

21st July 1917 Saturday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“On July 21st, we moved to another camp in a wood near St Sixte. It was a pleasant spot in a fir wood with lots of heather and mossy banks – not unlike a bit of old Scotland. The aeroplane activity was great as the weather was ideal. Any Hun planes that crossed our lines were soon driven back. Great numbers of captive balloons were up too, and our guns were unceasingly active. We were visited by the D.D.M.S. (Deputy Director Medical Services) 14th Corps in the afternoon. At night the Huns put over lots of high velocity shells, but did no damage.”

The diary of a Belgian priest, not too far away to the southwest of Poperinghe, near Dickebusch, also comments about the number of observation balloons he can see: twenty three British balloons and eight German ones. He also lamented the fact that today was Belgian Independence Day but there were no Belgian troops left in the area to celebrate in his Church.

Haig, however was feeling a little alarmed about a letter from The Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir William Robertson telling him that the Cabinet had not yet approved Haig’s plans for the forthcoming offensive. He wrote back complaining that the plans had been agreed as far back as the previous November, immediately after the official ending of the Battle of The Somme! Robertson, felt confident that although relations with the new Prime Minister Lloyd George were strained, approval would soon follow. This with arrangements pretty well advanced around Ypres.

In the Dickebusch area the day also saw a great deal of artillery action from both sides early in the morning and throughout the day, with some spectacular results as ammunition dumps were hit.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

19th July 1917 Thursday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

An ambulance trip through the build up of traffic for the next offensive

“Next day I got the job of going round the country collecting sick men for hospital in an ambulance car. I went out by International Corner, and saw many interesting sights, including five French armoured trains, hundreds of tanks, numbers of hospital trains, and new tent hospitals, large numbers of cavalry and many squads of Chinese and nigger labourers.”

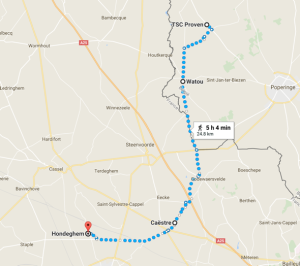

Douglas set out from Proven to drive around the neighbouring clearing stations and bears witness to what was the assembling of forces for the next “Big Push”. The area to the west of Ypres was a bustling collection of logistics as the Allies assembled troops and equipment around the area. Now only 12 days away from what was to be one of the war’s biggest actions and certainly the biggest since the relatively unsuccessful campaign on the Somme the previous year. Douglas’s comrades had taken such heavy losses on the Somme that they had been withdrawn from the front line, but were now preparing to rejoin the sharp end of business as now evidenced by build-up to the 3rd Battle of Ypres. General Haig had somehow managed to convince his bosses back in Whitehall that the awful losses of 1916 could be avoided this time with one more large offensive. The hope was that a swift decisive action would be more successful without such a great loss of life. The Americans had just entered the conflict and confidence amongst the Generals was high. Not so high though in the French Army whose men, depressed at the huge loss of life for little gain, and lack of pay had lost faith in their leaders and had begun widespread mutinies.

Over the border in France, but not far from Poperinghe British troops with the Chinese Labour Corps (Q 5895) Men of the Chinese Labour Corps at work in the timber yard at Caestre, 14 July 1917. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205237958

International Corner was at the intersection of where allied armies met. The new tent hospitals were in place to accept the expected casualties as were the new hospital trains. At Haig’s request in 1916, Chinese men were recruited into the Chinese Labour Corps and transported directly from the poverty stricken areas of China, with the lure of high or even regular wages. The end of 1917 would see 54000 of them in Flanders. The rise in number only halted by the British Navy being unable to guarantee transportation from China. Many other nationalities were recruited from throughout the British Empire including aboriginal Australians and many Africans and Indians. Many fought on the front line, but many just came as labour, building the infrastructure to serve the army.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

18th July 1917 Wednesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

The Franco/ Belgian border existed only on a map in the reality of the conflict in Flanders, so often was it crossed by troops of both sides. The early start was the commencement of a 25 km trek back to the area north-east of Poperinghe.

“We were up at 2.30 on the next morning, and moved off at 4 a.m., arriving at Proven via Caestre and Watou, about 11 o’clock in the forenoon. The whole area was stiff with troops and guns, and lots of new hospitals (a bad sign!) were in existence around Proven. Chinese troops were working at the rail-head at Proven.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

17th July 1917 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

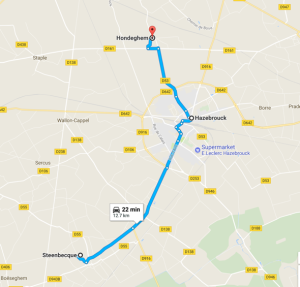

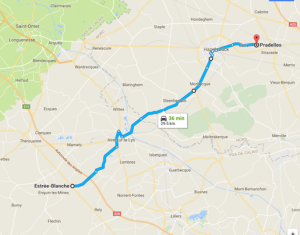

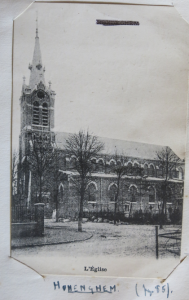

Continuing the theme of place names that don’t reflect the modern spelling, Douglas and his men left Steenbecque for Hondeghem, via Hazebrouck. In the modern world it would take about two and a half hours to walk the journey, giving some measure to the amount of congestion the men were encountering on the journey.

“On Tuesday 17th July we left at 8 a.m. for Honenghem, seven miles off. It took us four hours to reach our destination owing to the phenomenal amount of traffic on the roads. A whole Australian Army was on the move with us. We went through Hazebroucke. At Honenghem we messed in a farmhouse and slept in tents in an orchard. The weather was warm and sunny.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

15th July 1917 Sunday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“We left Estree-Blanche by motor bus (London buses) for Prandelles on Sunday July 15th. Sunday was a favourite day for moving us about, or having straffes! There were lots of troops on the move. Capt. Buchan came back from leave in the evening and I returned to the Field Ambulance, now stationed at Stenbecque – a small town full of troops including a whole Australian brigade.”

Below is an extract from the 13th Welsh diary. This highlights some of the spelling mistakes in the diary as to name places etc. Prandelles was in fact Pradelles and Stenbecque was Steenbecque, which is quite important when trying to locate places. It has been a recurring feature in the diary, possibly indicated that it was typed up from notes (now lost) by a third party. This coupled with official name changes and alterations that have evolved over the century since the war. This is not confined to this work, but is a slow process that takes place in all areas over time. The activities of estate agents is one source of this, along with natural movement and development. For instance, the area near Arsenal Stadium seems to have changed in recent years from Highbury Hill to Arsenal and is beginning to be reflected as such on modern maps. A naturally occurring phenomenon that just adds a degree of difficulty to the researcher’s work.

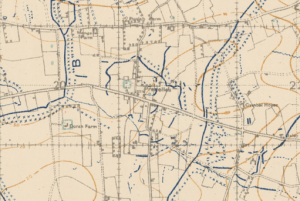

Pradelles on a British trench map 1918. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

July 1917 undated

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

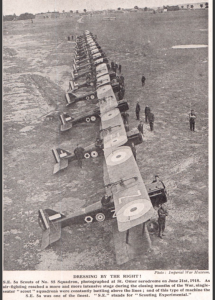

“There was a large aerodrome near us and all officers went up in planes for liaison work. I had a short flight too. It was most thrilling, but my pilot did the falling leaf stunt which upset my equilibrium for a day or two afterwards. At this aerodrome I saw several of the very latest fighting machines – single-seaters capable of flying at 160 mph and carrying two machine guns each.”

By 1917 military aircraft development had come quite a long way, probably thanks to the demands of war. The fastest machines available to the Royal Flying Corps at the time were the S.E. 5 and 5a. S.E. stood for Scouting Experimental and production at the new Royal Aircraft Factory in Farnborough, Hants., was in full swing. The S.E. had been designed to try and negate the high level of fatalities being inflicted on Britain’s inexperienced new young pilots. Being easier to fly, the S.E.5 became one of the war’s most successful aircraft, soon developed into the more powerful S.E.5a its single cockpit was augmented by two machine guns and had a service speed of 138 mph. It is no surprise therefore that the pilots had claimed to Douglas a top speed of 160 mph, as this might have been possible in a powered dive.

I am grateful to Mr. John Steward of the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust Museum for the photograph taken from his copy of “Twenty Years After. The Battlefields of 1914-18 Then and Now”.

You can learn more of the museum here. https://www.airsciences.org.uk

The machine that Douglas enjoyed his “falling leaf” adventure in is lost to history, but a likely contender was the two seat R.E.8 bi-plane that was ubiquitously employed on the Western Front for reconnaissance and light bombing duties. Over 4000 of them were produced during the war. It wasn’t the only type that he could have flown in but the sheer numbers of them make it a reasonable choice.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

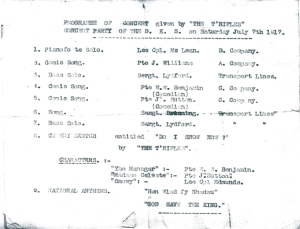

7th July 1917 Saturday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

Douglas Page made no mention of this in the diary, but luckily included a copy of the programme, giving us a small insight into the Saturday evening’s entertainment on the 7th.

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

3rd July 1917 Tuesday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“I got no rest, however, as I was packed off on Tuesday, July 3rd, to do duty with the 13th Welsh at Estree-Blanche. Capt. Buchan went off on leave in great form – of course. Col. Kennedy (Black Watch) was in command and I was billeted in the village post-office. My days were spent in lecturing to and training stretcher-bearers, and inspecting the men at the baths. I also attended with the Battalion at the training area, when the Brigade went through numerous rehearsals of the coming attack.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here

1st July 1917 Sunday

All material produced or reproduced here and throughout this work is the sole copyright of the author and the family of Doctor D.C.M. Page MC.

“On Sunday 1st July I returned for duty to the 130th Field Ambulance at Tiremonde – a small village. I was billeted in a tiny, but clean room in a cottage. The hospital consisted of tents pitched in an orchard – a pretty spot.”

Find out about our connection with Dr Page and an introduction to his diary here